Blockchain and smart contract commerce are expanding rapidly. Parties do business relying that software will execute transactions as intended. But software can be flawed, and one trading partner can behave in a way that the other partner did not expect.

Here is an example of an alleged software flaw that has given rise to a lawsuit: The owner of a non-fungible token says a flaw in NFT platform Oversea allowed a hacker to steal the NFT. In February the owner sued Oversea in federal court seeking compensation. McKimmy v. OpenSea (Civil Action No. 4:22-CV-00545) S. District of Texas.

Often, the legal expectations in a smart contract are not well articulated. Example from the Livepeer Web 3.0 ecosystem: The holder of an LPT token might "stake" the token with an orchestrator (node operator), expecting the financial returns advertised by the orchestrator.

Livepeer is based on Ethereum, but uses some words that are different from the usual words in Ethereum. Use of different words could cause legal confusion.

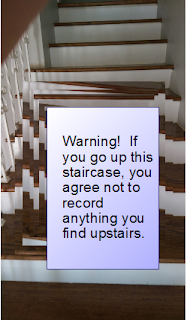

The precise, easy-to-understand legal relationship between the parties might not be stated anywhere. One response from the token holder would be unilaterally to communicate terms to the orchestrator.

The token holder might, for example, send an email to the orchestrator saying something roughly like this: "These are the terms on which I delegate (stake) my LPT token with you. You agree to these terms by moving forward with our relationship. You will give me rewards XYZ. You will provide me those rewards even if Livepeer software fails to deliver those rewards to me. Neither you nor your creditors may assert control over my token beyond what is considered as "staking" generally within the Ethereum community. If I successfully sue you to enforce these terms, you will pay my attorney's fees. These terms are governed by the law of the state of ABC."

Be careful when stating terms this way. A party like the token holder should not state terms that are unfair or onerous. The stated terms should honestly reflect the expectations of the parties based on the context. Fairness and honesty go to the core of good human relations (justice and human dignity) and are much more likely to win favor in court.

What do you think?

(This post is just for public discussion and not legal advice for any particular situation.)